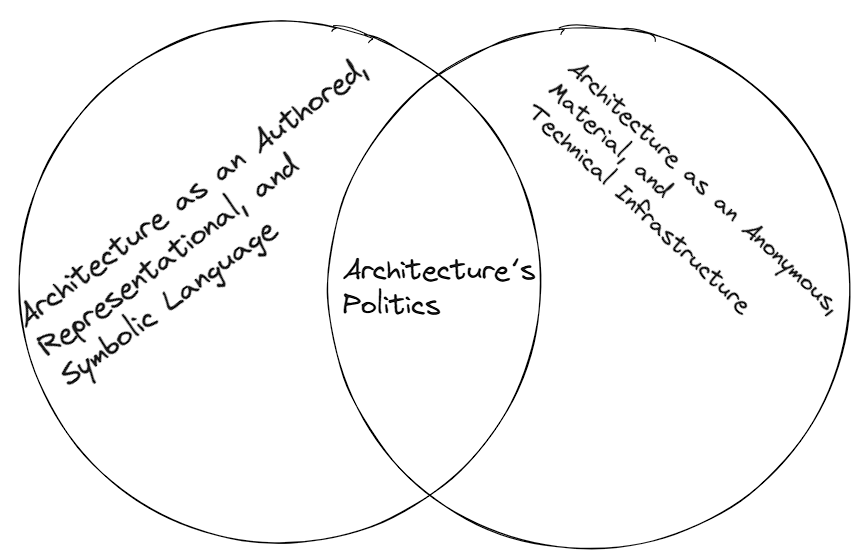

In today’s rapidly evolving world, the role of architecture extends far beyond mere buildings and structures; it is deeply intertwined with the social, cultural, and political fabric of our societies. Yet, a fundamental question persists: Should architecture be understood as an authored, representational, and symbolic language that communicates ideas and values, or as an anonymous, material, and technical infrastructure that shapes our daily lives in more subtle, yet profound, ways? This debate is not just academic—it strikes at the heart of how we interpret and engage with the built environment around us. As we seek to grasp the politics of architecture in the present moment, exploring this dichotomy offers crucial insights into the ways in which architecture influences, and is influenced by, the world we inhabit. In this blog post, we will delve into this question, examining the strengths and limitations of each perspective, and considering how a more integrated approach might provide a richer understanding of architecture’s political dimensions today.

Architecture as an Authored, Representational, and Symbolic Language

If we view architecture as an authored, representational, and symbolic language, we are acknowledging that buildings and spaces carry meanings beyond their physical form. This perspective sees architecture as a medium through which architects communicate ideas, values, and ideologies. It recognizes that architecture can be a powerful tool for expression, capable of conveying messages about culture, identity, power, and even resistance.

From this viewpoint, architects are seen as authors, much like writers or artists, who intentionally imbue their work with symbolism and meaning. For example, iconic structures like the Eiffel Tower or the Guggenheim Museum are not just functional spaces; they are also symbols of innovation, national pride, and artistic achievement. Similarly, monumental architecture such as government buildings or religious structures often represents the authority, beliefs, and aspirations of a society.

Understanding architecture in this way also allows us to analyze the ways in which buildings and spaces are used to assert power, control, and influence. The design of public spaces, for instance, can either promote inclusivity and democracy or reinforce social hierarchies and exclusion. This approach to architecture highlights the role of architects and designers as active participants in shaping the social and political landscape.

Architecture as an Anonymous, Material, and Technical Infrastructure

On the other hand, considering architecture as an anonymous, material, and technical infrastructure emphasizes its functional and practical aspects. This perspective views buildings and spaces primarily as solutions to practical problems—shelter, workspaces, transportation hubs, etc.—rather than as vehicles for symbolic communication. Here, the focus is on architecture’s materiality, construction techniques, and utility, rather than on its aesthetic or symbolic dimensions.

From this angle, the politics of architecture are understood through its impact on everyday life, often in ways that are not immediately visible or consciously recognized. The design of infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, or housing developments, influences how people move, interact, and live. Decisions about zoning, building codes, and urban planning shape the distribution of resources and opportunities, affecting who has access to what, and where.

This view also highlights the often-unseen labor and technical expertise that goes into creating and maintaining the built environment. It considers architecture as a collective and anonymous endeavor, where the contributions of engineers, builders, and planners are as important as those of the architect. The political implications of this perspective lie in the way these decisions and designs affect social equity, environmental sustainability, and the distribution of power.

Grasping Architecture’s Politics in the Present Moment

In the present moment, the most insightful approach to understanding the politics of architecture may lie in a synthesis of these two perspectives. The built environment is both a symbolic and representational language and a material and technical infrastructure. By recognizing this dual nature, we can better understand how architecture operates on multiple levels—both as a medium of communication and as a framework for daily life.

This holistic understanding allows us to see how architecture can reinforce or challenge social norms, influence behavior, and shape political outcomes. Whether through the symbolic power of a public monument or the practical implications of urban infrastructure, architecture plays a critical role in shaping the world we live in. To grasp its politics fully, we must consider both its authored, representational aspects and its anonymous, material dimensions, recognizing that each informs and influences the other.